Synergies in M&A

Attorneys with you, every step of the way

Count on our vetted network of attorneys for guidance — no hourly charges, no office visits.

2000+

businesses

Helping entrepreneurs turn ideas into

businesses over 2000+ times in Russia.

1500+

consultations

Providing access to our independent

network of attorneys over 1500 times.

90+

liquidations

Helping companies to close down operations in the smooth way

Synergies represent the estimated cost savings or incremental revenue arising from a merger or acquisition, which are often used by buyers to rationalize higher purchase price premiums.

The importance of synergies is tied to the fact that if an acquirer assumes more post-deal synergies can be realized, a higher purchase premium can be ascribed to the offer price.

Synergies Definition in M&A

In M&A, the underlying concept of synergies is based on the premise that the combined value of two entities is worth more than the sum of separately valued parts.

The post-deal assumption is that the performance of the combined company (and the implied valuation) will be positively impacted in the coming year(s).

One of the primary incentives for companies to pursue M&A in the first place is to generate synergies across the long run, which can result in a wide scope of potential benefits.

If a company worth $150m acquires another smaller-sized company that is worth $50m – yet post-combination, the combined company is valued at $250m, then the implied synergy value comes out to $50m.

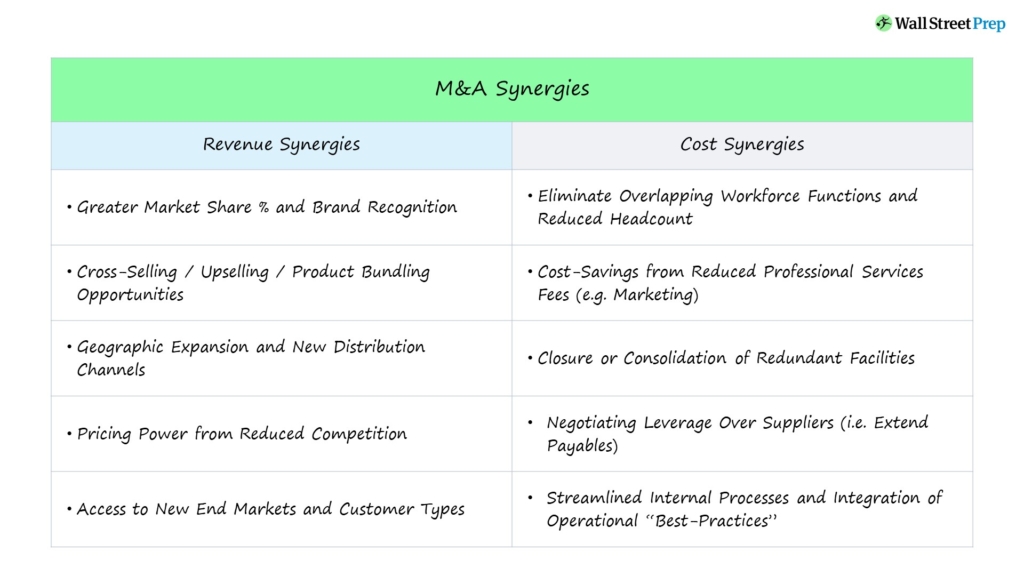

Revenue vs. Cost Synergies

What are Revenue Synergies?

Synergies, the financial benefits arising from the transaction, can be categorized as either revenue or cost synergies.

Revenue synergies are based on the assumption that the combined companies can generate more cash flows than if their individual cash flows were added together.

Hence, these benefits in M&A must be pitched as being mutually beneficial, as opposed to being one-sided exchanges.

But while viable in theory, revenue synergies often do not materialize, as these types of benefits are based on more uncertain assumptions surrounding cross-selling, new product/service introductions, and other strategic growth plans.

One important fact to consider is that capturing revenue synergies, on average, tends to require more time than achieving cost synergies – assuming the revenue synergies are indeed realized in the first place.

Often referred to as the “phase-in” period, synergies are typically realized two to three years post-transaction, as integrating two separate entities is a time-consuming, complex process, regardless of how compatible the two appear.

What are Cost Synergies?

The main reason for an acquisition is frequently related to cost-cutting in terms of consolidating overlapping R&D efforts, closing down manufacturing plants, and eliminating employee redundancies.

Unlike revenue synergies, cost synergies tend to be more likely to be realized and therefore are viewed as more credible, which is attributable to how cost synergies can point towards specific cost-cutting initiatives such as laying off workers and shutting down facilities.

Since synergies are challenging to achieve in practice, they should be estimated on a conservative basis, but doing so can result in potentially missing out on acquisition opportunities (i.e. getting out-bid by another buyer).

Studies have routinely shown how the majority of buyers overvalue the projected synergies stemming from an acquisition, which leads to paying a premium that may not have been justified (i.e. the “winners curse”).

Acquirers must often accept that the expected synergies used to justify a purchase price premium may not ever materialize.

Financial Synergies

Besides revenue and cost synergies, there are also financial synergies, which tend to be more of a gray area, as quantifying the benefits is more intricate relative to the other types. But some commonly cited examples are tax savings related to net operating losses (or NOLS), greater debt capacity, and a lower cost of capital.

Strategic Buyers vs Financial Buyers Purchase Premium

Strategic buyers are typically expected to be willing to pay greater premiums than financial buyers (i.e. private equity firms).

Since strategic buyers can often derive greater post-combination benefits, this allows them to offer higher purchase prices.

However, in recent years, the prevalence of add-on acquisitions has enabled financial buyers to fare better in competitive M&A auctions considering a platform company (i.e. the core portfolio company) can benefit from synergies upon merging with an add-on acquisition target, similar to a strategic buyer.

Organic vs. Inorganic Growth

Simply put, organic growth consists of the internal optimization of a company by its employees under the guidance of the management team.

For companies in the organic growth stage, management is actively reinvesting into:

- Better Understanding the Target Market

- Segmentation of Customers in a Cohort Analysis

- Expansion into Adjacent Markets

- Enhancement of Product/Service Offering Mix

- Improving Sales & Marketing (S&M) Strategies

- Introducing New Products to the Current Lineup

Here, the focus is on continuous operational improvements and bringing in revenue more efficiently, which can be achieved by setting prices more appropriately following market research and targeting the right end markets, to name a few examples.

However, at some point, opportunities for organic growth can gradually decline, which could force a company to rely on inorganic growth – which refers to growth driven by M&A.

Compared to organic growth strategies, inorganic growth is often considered to be the quicker (and more convenient) option.

Following an M&A deal, the companies involved can observe noticeable benefits within a short time span, such as being able to set up a channel to sell products to customers and bundling complementary products.

Goodwill Creation

Typically, acquirers pay more than the fair market value (FMV) of the target’s net identifiable assets – with goodwill representing the excess purchase price paid.

While there are numerous reasons for a premium to be included in the offer price, – the potential to achieve synergies – is often used to rationalize the purchase price premium.

Of course, this sort of reasoning could be right at times and lead to profitable returns, but other times, it could lead to overpayment.

However, overpaying for an asset tends to go hand-in-hand with the overestimation of the anticipated post-deal benefits.

M&A Transaction Assumptions

Suppose we’re tasked with evaluating a potential M&A deal, with our first step being to perform a precedent transactions analysis (i.e. “acquisition comps”) or premiums paid analysis.

As a standard modeling convention, reviewing comparable acquisitions can be a decent starting point and serve as a “sanity check” to ensure the implied control premium is not completely out-of-line with the premiums paid in similar deals.

Here, our transaction assumptions will be kept much simpler for illustrative purposes.

- Revenue Synergies (% of Combined): 5%

- % Revenue Synergies Gross Margin: 60%

- COGS Synergies (% Combined COGS): 20%

- OpEx Synergies (% Combined OpEx): 40%

Since the realization of the anticipated benefits requires time, it would be rather unrealistic to assume 100% of the potential synergies are immediately realized, starting from year one.

Therefore, the 5% revenue assumption represents the run rate that will be reached by Year 4 – which is often called the “phase-in” period in M&A.

- “Phase-In” Period (Year 1 to Year 4): 20% → 50% → 80% → 100%

Post-Deal Combined Financials

Next, we can see the projected revenue of the acquirer and target, which will be consolidated.

There are four sections listed, with each calculating the following:

- Combined Revenue

- Combined Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

- Combined Operating Expenses (OpEx)

- Combined Net Income (Post-Tax)

Revenue and Cost Synergies Calculation Example

To account for the synergies in the combined financials, we’ll multiply the synergy assumption listed at the top of the model by the combined revenue (the acquirer + target) – and then multiply that figure by the % of synergies realized assumption.

The following Excel formulas are used:

- Revenue Synergies = Revenue Synergies (% Combined) * SUM (Acquirer Revenue, Target Revenue) * (% Synergies Realized)

- Cost Synergies = – COGS Synergies (% Combined) * SUM (Acquirer COGS, Target COGS) * (% Synergies Realized)

- OpEx Synergies = – OpEx Synergies (% Combined) * SUM (Acquirer OpEx, Target OpEx) * (% Synergies Realized)

The calculations for each should be straightforward, but one important distinction to note is that the revenue synergies come along with a gross margin assumption in our model (Line 23).

Hence, acquirers tend to prefer cost synergies because such cost savings flow more directly to net income (i.e. the “bottom line”), with the only adjustment being for taxes.

In comparison, revenue synergies are reduced by the margin assumption prior to being taxed. For instance, the revenue synergies are estimated at $18m in Year 4, but the gross margin assumption of 60% causes the revenue synergies to come out at $7m.

- Year 4 Revenue Synergies = $18m – $11m = $7m

Note: There are numerous simplifications made throughout our model – to state the obvious, a full M&A analysis would account for an extensive list of adjustments (e.g. foregone interest, incremental D&A from write-ups).

Once each section is calculated and the 30% tax rate is applied to the combined pre-tax income, we arrive at the combined net income for the post-deal entity.

In closing, we can see how relative to revenue synergies, a higher portion of COGS and OpEx flows down to the net income line.