M&A deal structure

Attorneys with you, every step of the way

Count on our vetted network of attorneys for guidance — no hourly charges, no office visits.

Cash vs. Stock Acquisition (M&A)

In acquisitions, buyers usually pay the seller with cold, hard cash.

However, the buyer can also offer the seller acquirer stock as a form of consideration. According to Thomson Reuters, 33.3% of deals in the second half of 2016 used acquirer stock as a component of the consideration.

For example, when Microsoft and Salesforce were offering competing bids to acquire LinkedIn in 2016, both contemplated funding a portion of the deal with stock (“paper”). LinkedIn ultimately negotiated an all-cash deal with Microsoft in June 2016.

Why Pay with Acquirer Stock?

- For the acquirer, the main benefit of paying with stock is that it preserves cash. For buyers without a lot of cash on hand, paying with acquirer stock avoids the need to borrow in order to fund the deal.

- For the seller, a stock deal makes it possible to share in the future growth of the business and enables the seller to potentially defer the payment of tax on gain associated with the sale.

Below we outline the potential motivations for paying with acquirer stock:

Risk and Reward

In cash deals, the seller has cashed out. Barring some sort of “earn out,” what happens to the combined company – whether it achieves the synergies it hoped, whether it grows as expected, etc. — is no longer too relevant or important to the seller. In deals funded at least partially with stock, target shareholders do share in the risk and reward of the post-acquisition company. In addition, changes in acquirer stock-price fluctuations between deal announcement and close may materially impact the seller’s total consideration (more on this below).

Control

In stock deals, sellers transition from full owners who exercise complete control over their business to minority owners of the combined entity. Decisions affecting the value of the business are now often in the hands of the acquirer.

Financing

Acquirers who pay with cash must either use their own cash balances or borrow money. Cash-rich companies like Microsoft, Google and Apple don’t have to borrow to affect large deals, but most companies do require external financing. In this case, acquirers must consider the impact on their cost of capital, capital structure, credit ratios and credit ratings.

Tax

While tax issues can get tricky, the big-picture difference between cash and stock deals is that when a seller receives cash, this is immediately taxable (i.e. the seller must pay at least one level of tax on the gain). Meanwhile, if a portion of the deal is with acquirer stock, the seller can often defer paying tax. This is probably the largest tax issue to consider and as we’ll see shortly, these implications play prominently in the deal negotiations. Of course, the decision to pay with cash vs. stock also carries other sometimes significant legal, tax, and accounting implications.

Let’s take a look at a 2017 deal that will be partially funded with acquirer stock: CVS’s acquisition of Aetna. Per the CVS merger announcement press release:

dAetna shareholders will receive $145.00 per share in cash and 0.8378 CVS Health shares for each Aetna share.

Fixed Exchange Ratio Structure Adds to Seller Risk

In the CVS/AETNA deal consideration described above, notice that each AETNA shareholder receives 0.8378 CVS shares in addition to cash in exchange for one AETNA share. The 0.8378 is called the exchange ratio.

A key facet of stock deal negotiation is whether the exchange ratio will be fixed or floating. Press releases usually address this as well, and CVS’s press release is no exception:

The transaction values Aetna at approximately $207 per share or approximately $69 billion [Based on (CVS’) 5-day Volume Weighted Average Price ending December 1, 2017 of $74.21 per share… Upon closing of the transaction, Aetna shareholders will own approximately 22% of the combined company and CVS Health shareholders will own approximately 78%.

While more digging into the merger agreement is needed to confirm this, the press release language above essentially indicates that the deal was structured as a fixed exchange ratio. This means that no matter what happens to the CVS share price between the announcement date and the closing date, the exchange ratio will stay at 0.8378. If you’re an AETNA shareholder, the first thing you should be wondering when you hear this is “What happens if CVS share prices tank between now and closing?”

That’s because the implication of the fixed exchange ratio structure is that the total deal value isn’t actually defined until closing, and is dependent on CVS share price at closing. Note how the deal value of $69 billion quoted above is described as “approximately” and is based on the CVS share price during the week leading up to the deal closing (which will be several months from the merger announcement). This structure isn’t always the case — sometimes the exchange ratio floats to ensure a fixed transaction value.

Strategic vs. Financial Buyers

It should be noted that the cash vs. stock decision is only relevant to “strategic buyers.”

- Strategic Buyer: A “strategic buyer” refers to a company that operates in or is looking to get into, the same industry as the target it seeks to acquire.

- Financial Buyer: “Financial buyers,” on the other hand, refers to private equity investors (“sponsor backed” or “financial buyers”) who typically pay with cash (which they finance by putting in their own capital and borrowing from banks).

Exchange Ratios in M&A

For a deal structured as a stock sale (as opposed to when the acquirer pays with cash — read about the difference here), the exchange ratio represents the number of acquirer shares that will be issued in exchange for one target share. Since acquirer and target share prices can change between the signing of the definitive agreement and the closing date of a transaction, deals are usually structured with:

- A fixed exchange ratio: the ratio is fixed until closing date. This is used in a majority of U.S. transactions with deal values over $100 million.

- A floating exchange ratio: The ratio floats such that the target receives a fixed value no matter what happens to either acquirer or target shares.

- A combination of a fixed and floating exchange, using caps and collars.

The specific approach taken is decided in the negotiation between buyer and seller. Ultimately, the exchange ratio structure of the transaction will determine which party bears most of the risk associated with pre-close price fluctuation. BThe differences described above can be broadly summarized as follows:

| Fixed exchange ratio | Floating exchange ratio |

|---|---|

| Shares issued are knownValue of transaction is unknownPreferred by acquirers because the issuance of a fixed number of shares results in a known amount of ownership and earnings accretion or dilution | Value of transaction is knownShares issued are unknownPreferred by sellers because the deal value is defined (i.e. the seller knows exactly how much it is getting no matter what) |

Fixed exchange ratio

Below is a fact pattern to demonstrate how fixed exchange ratios work.

Terms of the agreement

- The target has 24 million shares outstanding with shares trading at $9; The acquirer shares are trading at $18.

- On January 5, 2014 (“announcement date”) the acquirer agrees that, upon completion of the deal (expected to be February 5, 2014) it will exchange .6667 of a share of its common stock for each of the target’s 24 million shares, totaling 16m acquirer shares.

- No matter what happens to the target and acquirer share prices between now and February 5, 2014, the share ratio will remain fixed.

- On announcement date, the deal is valued at: 16m shares * $18 per share = $288 million. Since there are 24 million target shares, this implies a value per target share of $288 million/24 million = $12. That’s a 33% premium over the current trading price of $9

Acquirer share price drops after announcement

- By February 5, 2014, the target’s share price jumps to $12 because target shareholders know that they will shortly receive .6667 acquirer shares (which are worth $18 * 0.6667 = $12) for each target share.

- What if, however, the value of acquirer shares drop after the announcement to $15 and remain at $15 until closing date?

- The target would receive 16 million acquirer shares and the deal value would decline to 16 million * $15 = $240 million. Compare that to the original compensation the target expected of $288 million.

Bottom line: Since the exchange ratio is fixed, the number of shares the acquirer must issue is known, but the dollar value of the deal is uncertain.

Floating exchange (fixed value) ratio

While fixed exchange ratios represent the most common exchange structure for larger U.S. deals, smaller deals often employ a floating exchange ratio. Fixed value is based upon a fixed per-share transaction price. Each target share is converted into the number of acquirer shares that are required to equal the predetermined per-target-share price upon closing.

Let’s look at the same deal as above, except this time, we’ll structure it with a floating exchange ratio:

- Target has 24 million shares outstanding with shares trading at $12. Acquirer shares are trading at $18.

- On January 5, 2014 the target agrees to receive $12 from the acquirer for each of target’s 24 million shares (.6667 exchange ratio) upon the completion of the deal, which is expected happen February 5, 2014.

- Just like the previous example, the deal is valued at 24m shares * $12 per share = $288 million.

- The difference is that this value will be fixed regardless of what happens to the target or acquirer share prices. Instead, as share prices change, the amount of acquirer shares that will be issued upon closing will also change in order to maintain a fixed deal value.

While the uncertainty in fixed exchange ratio transactions concerns the deal value, the uncertainty in floating exchange ratio transactions concerns the number of shares the acquirer will have to issue.

- So what happens if, after the announcement, the acquirer shares drop to $15 and remain at $15 until the closing date?

- In a floating exchange ratio transaction, the deal value is fixed, so the number of shares the acquirer will need to issue remains uncertain until closing.

Collars and caps

Collars may be included with either fixed or floating exchange ratios in order to limit potential variability due to changes in acquirer share price.

Fixed exchange ratio collar

Fixed exchange ratio collars set a maximum and minimum value in a fixed exchange ratio transaction:

- If acquirer share prices fall or rise beyond a certain point, the transaction switches to a floating exchange ratio.

- Collar establishes the minimum and maximum prices that will be paid per target share.

- Above the maximum target price level, increases in the acquirer share price will result in a decreasing exchange ratio (fewer acquirer shares issued).

- Below the minimum target price level, decreases in the acquirer share price will result in an increasing exchange ratio (more acquirer shares issued).

Floating exchange ratio collar

The floating exchange ratio collar sets a maximum and minimum for numbers of shares issued in a floating exchange ratio transaction:

- If acquirer share prices fall or rise beyond a set point, the transaction switches to a fixed exchange ratio.

- Collar establishes the minimum and maximum exchange ratio that will be issued for a target share.

- Below a certain acquirer share price, exchange ratio stops floating and becomes fixed at a maximum ratio. Now, a decrease in acquirer share price results in a decrease in value of each target share.

- Above a certain acquirer share price, the exchange ratio stops floating and becomes fixed at a minimum ratio. Now, an increase in acquirer share price results in an increase in the value of each target share, but a fixed number of acquirer shares is issued.

Walkaway rights

- This is another potential provision in a deal that allows parties to walk away from the transaction if acquirer stock price falls below a certain predetermined minimum trading price.

Earnouts in M&A

What is an Earnout?

An earnout, formally called a contingent consideration, is a mechanism used in M&A whereby, in addition to an upfront payment, future payments are promised to the seller upon the achievement of specific milestones (i.e. achieving specific EBITDA targets). The purpose of the earnout is to bridge the valuation gap between what a target seeks in total consideration and what a buyer is willing to pay.

Types of earnouts

Earnouts are payments to the target that are contingent on satisfying post-deal milestones, most commonly the target achieving certain revenue and EBITDA targets. Earnouts can also be structured around the achievement of non-financial milestones such as winning FDA approval or winning new customers.

A 2017 study conducted by SRS Acquiom looked at 795 private-target transactions and observed:

- 64% of deals had earnouts and revenue milestones

- 24% of deals had earnouts had EBITDA or earnings milestones

- 36% of deals had earnouts had some other kind of earnout metric (gross margin, achievement of sales quota, etc.)

Prevalence of earnouts

The prevalence of earnouts also depends on whether the target is private or public. Only 1% of public-target acquisitions include earnouts1 compared with 14% of private-target acquisitions2.

There are two reasons for this:

- Information asymmetries are more pronounced when a seller is private. It is generally more difficult for a public seller to materially misrepresent its business than it is for a private seller because public companies must provide comprehensive financial disclosures as a basic regulatory requirement. This ensures greater controls and transparency. Private companies, particularly those with smaller shareholder bases, can more easily hide information and prolong information asymmetries during the due diligence process. Earnouts can resolve this type of asymmetry between the buyer and seller by reducing the risk for the buyer.

- The share price of a public company provides an independent signal for target’s future performance. This sets a floor valuation which in turn narrows the range of realistic possible purchase premiums. This creates a valuation range that is usually far narrower than that observed in private target negotiations.

The prevalence of earnouts also depends on the industry. For example, earnouts were included in 71% of private-target bio pharmaceutical deals and 68% of medical device deals transactions transactions2. The high usage of earnouts in these two industries in not surprising since the company value can be quite dependent on milestones related to success of trials, FDA approval, etc.

Earnout in M&A example

Sanofi’s 2011 acquisition of Genzyme illustrates how earnouts can help parties reach agreement on valuation issues. On February 16, 2011, Sanofi announced it would acquire Genzyme. During negotiations, Sanofi was unconvinced of Genzyme’s claims that prior production issues around several of its drugs had been fully resolved, and that a new drug in the pipeline was going to be as successful as advertised. Both parties bridged this valuation gap as follows:

- Sanofi would pay $74 per share in cash at closing

- Sanofi would pay an additional $14 per share, but only if Genzyme achieved certain regulatory and financial milestones.

In the Genyzme deal announcement press release (filed as an 8K the same day), all the specific milestones required to achieve the earnout were identified and included:

- Approval milestone: $1 once FDA approved Alemtuzumab on or before March 31, 2014.

- Production milestone: $1 if at least 79,000 units of Fabrazyme and 734,600 units of Cerezyme were produced on or before December 31, 2011.

- Sales milestones: The remaining $12 would be paid out contingent to Genzyme achieving four specific sales milestones for Alemtuzumab (all four are outlined in the press release).

Genzyme did not end up achieving the milestones and sued Sanofi, claiming that as the company’s owner, Sanofi didn’t do its part to make the milestones achievable.

Tender Offer vs. Merger

A statutory merger (aka “traditional” or “one step” merger)

A traditional merger is the most common type of public acquisition structure. A merger describes an acquisition in which two companies jointly negotiate a merger agreement and legally merge.

Target shareholder approval is required

The target board of directors initially approves the merger and it subsequently goes to a shareholder vote. Most of the time a majority shareholder vote is sufficient, although some targets require a supermajority vote per their incorporation documents or applicable state laws.

In practice

Over 50% of all US companies are incorporated in Delaware, where majority voting is the law.

Buyer shareholder approval required when paying with > 20% stock

An acquirer can either use cash or stock or a combination of both as the purchase consideration. An acquirer may also need shareholder approval if it issues more than 20% of its stock in the deal. That’s because the NYSE, NASDAQ and other exchanges require it. Buyer shareholder vote is not required if the consideration is in cash or less than 20% of acquirer stock is issued in the transaction.

Example of a merger (one-step merger)

Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn in June 2016 is an example of a traditional merger: LinkedIn management ran a sell-side process and invited several bidders including Microsoft and Salesforce. LinkedIn signed a merger agreement with Microsoft and then issued a merger proxy soliciting shareholder approval (no Microsoft shareholder approval was required since it was an all-cash deal).

The primary advantage of structuring a deal as a merger (as opposed to the two-step or tender offer structure we’ll describe below) is that acquirer can get 100% of the target without having to deal with each individual shareholder – a simple majority vote is sufficient. That’s why this structure is common for acquiring public companies.

Legal mechanics of a merger

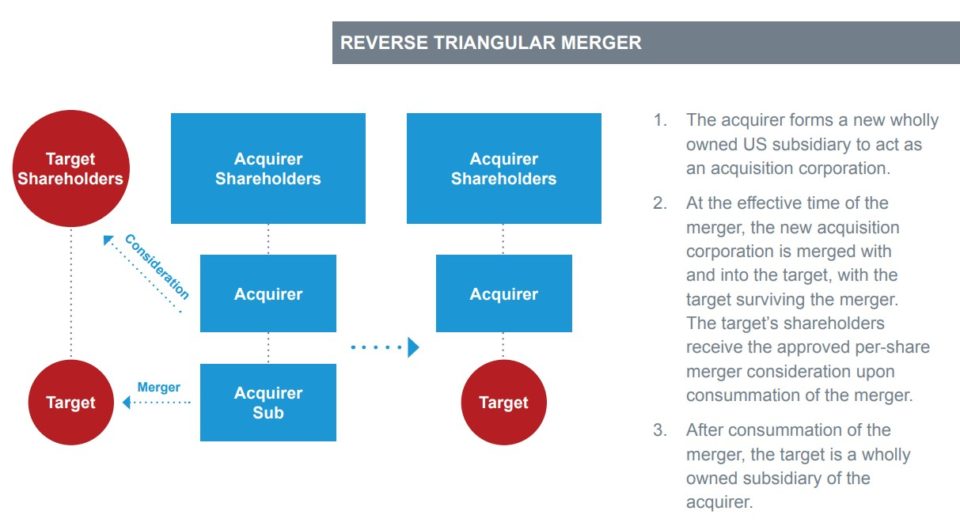

After the target shareholders approve the merger, target stock is delisted, all shares are exchanged for cash or acquirer stock (in LinkedIn’s case it was all cash), and target shares are cancelled. As a legal fine point, there are several ways to structure a merger. The most common structure is a reverse triangular merger (aka reverse subsidiary merger), in which the acquirer sets up a temporary subsidiary into which the target is merged (and the subsidiary is dissolved):

Tender offer or exchange offer (aka “two-step merger”)

In addition to the traditional merger approach described above, an acquisition can also be accomplished with the buyer simply acquiring the shares of the target by directly and publicly offering to acquire them. Imagine that instead of an acquirer negotiating with LinkedIn management, they simply went directly to shareholders and offered them cash or stock in exchange for each LinkedIn share. This is called a tender offer (if the acquirer offers cash) or an exchange offer (if the acquirer is offering stock).

- Main advantage: Acquirers can bypass the seller’s management and board

One distinct advantage of purchasing stock directly is that it allows buyers to bypass management and the board of directors entirely. That’s why hostile takeovers are almost always structured as a stock purchase. But a stock purchase can be attractive even in a friendly transaction in which there are few shareholders, accelerating the process by avoiding the otherwise required management and board meetings and shareholder vote. - Main disadvantage: Acquirers have to deal with potential holdouts

The challenge with purchasing target stock directly is that to gain 100% control of the company, the acquirer must convince 100% of the shareholders to sell their stock. If there are holdouts (as there almost certainly would be for companies with a diffuse shareholder base), the acquirer can also gain control with a majority of shares, but it will then have minority shareholders. Acquirers generally prefer not to deal with minority shareholders and often seek to gain 100% of the target.

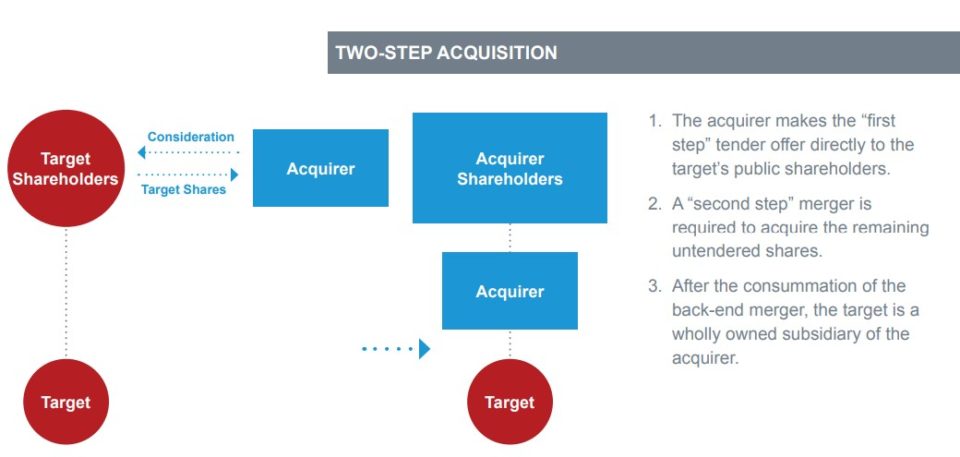

Two-step merger

Barring a highly concentrated shareholder base which would facilitate a complete 100% purchase in one step (workable for private targets with a few shareholders that can be directly negotiated with), stock purchases are affected via what’s called a two-step merger. The first step is the tender (or exchange) offer, where the buyer seeks to achieve a majority ownership, and the second step seeks to get ownership to 100%. In this step, the acquirer needs to reach a certain ownership threshold that legally empowers it to squeeze out minority shareholders (illustrated below).

Step one: tender offer or exchange offer

To initiate the tender offer, the buyer will send an “Offer to Purchase” to each shareholder and file a Schedule TO with the SEC with the tender offer or exchange offer attached as an exhibit. In response, the target must file its recommendation (in schedule 14D-9) within 10 days. In a hostile takeover attempt, the target will recommend against the tender offer. This is where you may see the rare fairness opinion that claims a transaction isn’t fair.

The buyer will condition their commitment to follow through with the purchase on reaching a certain threshold of target shareholder participation by a specified date (usually at least 20 days from the tender offer). Usually that threshold is a majority (> 50%), which is the minimum required to legally move to the next step without having to negotiate with minority shareholders.

Step two: back-end (or “squeeze out”) merger

Achieving at least 50% ownership after the tender offer enables the acquirer to proceed with a back-end merger (squeeze out merger), a second step which forces the minority shareholders to convert their shares for the consideration offered by the acquirer.

Long form merger

When more than 50% but less than 90% of shares were acquired in the tender offer, the process is called a long form merger and involves additional filing and disclosure requirements on the part of the acquirer. A successful outcome for the acquirer, however, is generally assured; it just takes a while.

Short form merger

Most states allow an acquirer that has been able to purchase at least 90% of the seller stock through the tender offer to get the remainder quickly in a second step without onerous additional SEC disclosures and without having to negotiate with the minority shareholders in what’s called a short form merger.

“If a buyer acquires less than 100% (but generally at least 90%) of a target company’s outstanding stock, it may be able to use a short-form merger to acquire the remaining minority interests. The merger allows the buyer to acquire those interests without a stockholder vote, thereby purchasing all of the target company’s stock. This merger process occurs after the stock sale closes, and is not a negotiated transaction.”

Source: Thomas WestLaw

Notably, Delaware allows acquirers (upon meeting certain conditions) to do a short form merger with just majority (> 50%) ownership. This allows acquirers to bypass shareholder approval at the 50% threshold rather than 90%. Most other states still require 90%.

Breakup Fees and Reverse Termination Fees in M&A

Breakup fees

A breakup fee refers to a payment a seller owes a buyer should a deal fall through due to reasons explicitly specified in the merger agreement. For example, when Microsoft acquired LinkedIn in June 13, 2016, Microsoft negotiated a $725 million breakup fee should any of the following happen:

- LinkedIn Board of Directors changes its mind

- More than 50% of company’s shareholders don’t approve the deal

- LinkedIn goes with a competing bidder (called an “interloper”)

Breakup fees protect buyers from very real risks

There’s good reason for buyers to insist on a breakup fees: The target board is legally obligated to try to get the best possible value for their shareholders. That means that if a better offer comes along after a deal is announced (but not yet completed), the board might be inclined, due to its fiduciary obligation to target shareholders, to reverse its recommendation and support the new higher bid.

The breakup fee seeks to neutralize this and protect the buyer for the time, resources and cost already poured into the process.

This is particularly acute in public M&A deals where the merger announcement and terms are made public, enabling competing bidders to emerge. That’s why breakup fees are common in public deals, but not common in middle market deals.

IN PRACTICE

Breakup fees usually range from 1-5% of the transaction value.

Reverse termination fees

While buyers protect themselves via breakup (termination) fees, sellers often protect themselves with reverse termination fees (RTFs). As the name suggests, RTFs allow the seller to collect a fee should the buyer walk away from a deal.

Risks faced by the seller are different from the risks faced by the buyer. For example, sellers generally don’t have to worry about other bidders coming along to spoil a deal. Instead, sellers are usually most concerned with:

- Acquirer not being able to secure financing for the deal

- Deal not getting antitrust or regulatory approval

- Not getting buyer shareholder approval (when required)

- Not completing the deal by a certain date (“drop dead date”)

For example, when Verizon Communications acquired Vodafone’s interest in Verizon Wireless in 2014, Verizon Communications agreed to pay a $10 billion RTF should it be unable to secure financing for the purchase.

However, in the Microsoft/LinkedIn deal we referenced earlier, LinkedIn did not negotiate an RTF. That’s likely because financing (Microsoft has $105.6 billion in cash on hand) and antitrust trust concerns were minimal.

Reverse termination fees are most prevalent with financial buyers

Concerns about securing financing tend to be most common with financial buyers (private equity), which explains why RTFs are prevalent in non-strategic deals (i.e. the buyer is private equity).

A Houlihan Lokey survey looking at 126 public targets found that an RTF was included in only 41% of deals with a strategic buyer but included in 83% of deals with a financial buyer. In addition, the fees as a percentage of the target enterprise value are also higher for financial buyers: 6.5% as compared to 3.7% for strategic buyers.

The reason for the higher fees is that during the financial crisis, RTFs were set too low (1-3% of deal value), so private equity buyers found it was worth paying the fine to walk away from companies in meltdown.

RTF + specific performance

In addition to the RTF, and perhaps more importantly, sellers have demanded (and largely received) the inclusion of a provision called “conditional specific performance.” Specific performance contractually empowers the seller to force the buyer to do what the agreement requires, hence making it much harder for private equity buyers to get out of a deal.

“allows a seller to “specifically enforce (1) the buyer’s obligation to use its efforts to obtain the debt financing (in some cases, including by suing its lenders if necessary) and (2) in the event that the debt financing could be obtained using appropriate efforts, to force the buyer to close. Over the past several years, that approach has become the dominant market practice to address financing conditionality in private equity-led leveraged acquisitions.

Source: Debevosie & Plimption, Private Equity Report, Vol 16, Number 3

Both RTF and the conditional specific performance provisions are now the prevalent way that sellers protect themselves – especially with financial buyers.

No-Shop and Go-Shop Provision in M&A

The no-shop provision

When Microsoft acquired Linkedin on June 13, 2016, the press release disclosed that the breakup fee would take effect if LinkedIn ultimately consummates a deal with another buyer. Page 56 of the Microsoft/LinkedIn merger agreement describes in detail the limitation on LinkedIn’s ability to solicit other offers during the period between when the merger agreement was signed and when the deal will close.

This section of the merger agreement is called “No Solicitation,” and is more commonly known as a “no-shop” provision. No-shops are designed to protect the buyer from the seller continuing to accept bids and using the buyer’s bid to improve its position elsewhere.

In practice

No-shops are included in the majority of deals.

For Linkedin, the violation of the no-shop would trigger a $725 million breakup fee. According to M&A law firm Latham & Watkins, no-shops typically prevent the target from conducting the following activities in the period between signing and closing:

- Soliciting alternative acquisition proposals

- Offering information to potential buyers

- Initiating or encouraging discussions with potential buyers

- Continuing ongoing discussions or negotiations

- Waiving outstanding standstill agreements with third parties (this makes it harder for losing bidders to come back in)

Superior proposal

While no-shops place severe limitations on shopping the deal, target boards have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize offer value for shareholders, so they generally cannot refuse to respond to unsolicited offers.

That’s why the no-shop clause almost always has an exception around unsolicited superior offers. Namely, if target determines that the unsolicited offer is likely to be “superior,” it can engage. From LinkedIn’s merger proxy:

A “superior proposal” is a bona fide written acquisition proposal … for an acquisition transaction on terms that the LinkedIn Board has determined in good faith (after consultation with its financial advisor and outside legal counsel) would be more favorable from a financial point of view than the merger. …

The buyer usually has the right to match the offer and to gain full visibility on the discussions:

… and taking into account any revisions to the merger agreement made or proposed by Microsoft prior to the time of such determination and after taking into account the other factors and matters deemed relevant in good faith by the LinkedIn Board, including the identity of the person making the proposal, the likelihood of consummation, and the legal, financial (including financing terms), regulatory, timing and other aspects of the proposal.

Of course, if the superior proposal is accepted, LinkedIn still has to pay the termination fee (which means any offer must be sufficiently superior as to be worth the termination fee):

LinkedIn is not entitled to terminate the merger agreement to enter into an agreement for a superior proposal unless it complies with certain procedures in the merger agreement, including engaging in good faith negotiations with Microsoft during a specified period. If LinkedIn terminates the merger agreement in order to accept a superior proposal, it must pay a $725 million termination fee to Microsoft.

In the Microsoft/LinkedIn acquisition, the no-shop was an important part of the negotiation, as Microsoft was weary of other suitors, namely Salesforce. Ultimately, the no-shop held, but it did not prevent Salesforce from trying to come in with a higher unsolicited proposal bid for LinkedIn after the deal, forcing Microsoft to up the ante.

The go-shop provision

The vast majority of deals have no-shop provisions. However, there is an increasing minority of deals in which targets are allowed to shop around for higher bids after the deal terms are agreed upon.

In practice

Go-shops generally generally only appear when the buyer is a financial buyer (PE firm) and the seller is a private company. They are increasingly popular in go-private transactions, where a public company undergoes an LBO. A 2017 study conducted by law firm Weil reviewed 22 go-private transactions with a purchase price above $100 million and found that 50% included a go-shop provision.

Go-shops allows sellers to seek competitive bids despite an exclusive negotiation

From target shareholders’ point of view, the ideal way to sell is to run a sell-side process in which the company solicits several buyers in an effort to maximize the deal value. That happened (somewhat) with LinkedIn – there were several bidders.

But when the seller doesn’t run a “process” – meaning when it engages with a single buyer only — it is vulnerable to arguments that it did not meet its fiduciary responsibility to shareholders by failing to see what else is out there.

When this is the case, the buyer and seller can negotiate a go-shop provision which, in contrast to the no-shop, gives the seller the ability to actively solicit competing proposals (usually for 1-2 months) while keeping it on the hook for a lower breakup fee should a superior proposal emerge.

Do go-shops actually do what they’re supposed to?

Since the go-shop provision rarely leads to an additional bidder emerging, it is often criticized as being “window dressing” that stacks the deck in favor of the incumbent buyer. However, there have been exceptions where new bidders have emerged.

Material Adverse Change (MACs)

A Material Adverse Change (MAC) is one of several legal mechanisms used to reduce risk and uncertainty for buyers and sellers during the period between the date of the merger agreement and the date the deal closes.

MACs are legal clauses that buyers include in virtually all merger agreements that outline conditions that might conceivably give the buyer the right to walk away from a deal. Other deal mechanisms that address the gap-period risks for buyers and sellers include no-shops and purchase price adjustments as well as break up fees and reverse termination fees.

Introduction to Material Adverse Changes (MACs)

Role of MAC Clauses in M&A

In our guide to mergers & acquisitions, we saw that when Microsoft acquired LinkedIn on June 13, 2016, it included a $725 million break-up fee that LinkedIn would owe Microsoft if LinkedIn changed its mind prior to the closing date.

Notice that the protection given to Microsoft via the breakup fee is one-directional — there are no breakup fees owed to LinkedIn should Microsoft walk away. That’s because the risk that Microsoft will walk away is lower. Unlike LinkedIn, Microsoft doesn’t need to get shareholder approval. A common source of risk for sellers in M&A, especially when the buyer is a private equity buyer, is the risk that buyer can’t secure financing. Microsoft has ample cash, so securing financing isn’t an issue.

That’s not always the case, and sellers often protect themselves with reverse termination fees.

However, that doesn’t mean Microsoft can simply walk away for no reason. At the deal announcement, the buyer and seller both sign the merger agreement, which is a binding contract for both the buyer and seller. If the buyer walks away, the seller will sue.

So are there any circumstances in which the buyer can walk away from the deal? The answer is yes. … kind of.

The ABCs of MACs

In an effort to protect themselves against unforeseen changes to the target’s business during the gap period, virtually all buyers will include a clause in the merger agreement called the material adverse change (MAC) or material adverse effect (MAE). The MAC clause gives the buyer the right to terminate the agreement if the target experiences a material adverse change to the business.

Unfortunately, what constitutes a material adverse change is not clear cut. According to Latham & Watkins, courts litigating MAC claims focus on whether there is substantial threat to overall earnings (or EBITDA) potential relative to past performance, not projections. The threat to EBITDA is typically measured using long-term perspective (years, not months) of a reasonable buyer, and the buyer bears the burden of proof.

Unless the circumstances that trigger a MAC are very well defined, courts generally are loath to allow acquirers to back out of a deal via a MAC argument. That said, acquirers still like to include a MAC clause to improve their bargaining position with a litigation threat should problems with the target emerge post announcement.

Real-World M&A Example of MACs

As one might imagine, during the financial meltdown in 2007-8, many acquirers tried to back out of deals in which the targets were melting down using the MAC clause. These attempts were largely denied by courts, with Hexion’s acquisition of Huntsman being a good example.

Hexion tried to back out of the deal by claiming a material adverse change. The claim didn’t hold up in court and Hexion was forced to compensate Huntsman handsomely.

Exclusions in MACs

MACs are heavily negotiated and are usually structured with a list of exclusions that don’t qualify as material adverse changes. Perhaps the largest difference between a buyer-friendly and seller-friendly MAC is that the seller friendly MAC will carve out a large number of detailed exceptions of events that do NOT qualify as a material adverse change.

For example, the exclusions (events that explicitly won’t count as triggering a MAC) in the LinkedIn deal (p.4-5 of the merger agreement) include:

- Changes in general economic conditions

- Changes in conditions in the financial markets, credit markets or capital markets

- General changes in conditions in the industries in which the Company and its Subsidiaries conduct business, changes in regulatory, legislative or political conditions

- Any geopolitical conditions, outbreak of hostilities, acts of war, sabotage, terrorism or military actions

- Earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis, tornadoes, floods, mudslides, wild fires or other natural disasters, weather conditions

- Changes or proposed changes in GAAP

- Changes in the price or trading volume of the Company common stock

- Any failure, in and of itself, by the Company and its Subsidiaries to meet (A) any public estimates or expectations of the Company’s revenue, earnings or other financial performance or results of operations for any period

- Any transaction litigation

Deal Accounting in M&A

Acquisition accounting has always been a challenge for analysts and associates. I think it’s partly because the presentation of purchase accounting (the method prescribed under US GAAP and IFRS for handling acquisitions) in financial models conflates several accounting adjustments, so when newbie modelers are thrown into the thick of it, it becomes challenging to really understand all the moving parts.

Similar to the previous article where we covered LBO analysis, the goal of this article is to provide a clear, step-by-step explanation of the basics of acquisition accounting in the simplest way possible. If you understand this, all the complexities of acquisition accounting become much easier to grasp. As with most things finance, really understanding the basic building blocks is hugely important for mastery of more complex topics.

For a deeper dive into M&A modeling, enroll in our Premium Package or attend a financial modeling boot camp.

Deal Accounting: 2-Step Process Example

Bigco wants to buy Littleco, which has a book value (assets, net of liabilities) of $50 million. Bigco is willing to pay $100 million.

Why would acquirer be willing to pay $100 million for a company whose balance sheet tells us it’s only worth $50 million? Good question – maybe because the balance sheet carrying values of the assets don’t really reflect their true value; maybe the acquirer company is overpaying; or maybe it’s something else entirely. Either way, we’ll discuss that in a little while, but in the meantime, let’s get back to the task at hand.

Step 1: Pushdown Accounting (Purchase Price Allocation)

In the context of an acquisition, the target company’s assets and liabilities are written up to reflect the purchase price. In other words, since Bigco is willing to buy Littleco for $100 million, in FASB’s eyes, that’s the new book value of Littleco. Now the question becomes how do we allocate this purchase price to the assets and liabilities of Littleco appropriately? The example below will illustrate:

Fact Pattern:

- Bigco buys Littleco for $100 million

- Fair market value of Littleco PP&E is $60 million

- Bigco finances the acquisition by giving Littleco shareholders $40 million worth of Bigco stock and $60 million in cash, which it raises by borrowing.

- In an acquisition, assets and liabilities can be marked up (or down) to reflect their fair market value (FMV).

- In an acquisition, the purchase price becomes the target co’s new equity. The excess of the purchase price over the FMV of the equity (assets – liabilities is captured as an asset called goodwill.

Under purchase accounting, the purchase price is first allocated to the book values of the assets, net of liabilities. In this case, we can allocate $50 million of the $100 million purchase price to these book values, but there is a remaining excess of $50 million that needs to be allocated. The next step is to allocate the excess purchase price to the FMV of any assets / liabilities. In this case, the only asset that has a FMV different from its book value is PP&E ($60 vs. $50 million), so we can allocate another $10 million to PP&E.

At this point we have allocated $60 million of the $100 million purchase price and we’re stuck: Under accounting rules we cannot write up assets above their FMV, but we know that our balance sheet somehow has to reflect a $100 million book value (the purchase price). The accounting answer to this is goodwill. Goodwill is a truly intangible asset that captures the excess of the purchase price over the FMV of a company’s net assets. Another way to think of it is FASB saying to Bigco “we don’t know why you’d pay $100 million for this company, but you must have a reason for it – you can capture that reason in an intangible asset called goodwill.” So that’s it – we have “pushed down” the purchase price onto the target, and we are ready for the next step: combining the adjusted target balance sheet with the acquirer’s:

Step 2: Financial Statement Consolidation (Post-Deal)

Consolidation Recall that Bigco finances the acquisition by giving Littleco shareholders $40 million worth of Bigco stock and $60 million in cash. That’s what it will cost to buy out Littleco shareholders:

(3) Acquirer can finance the acquisition with debt, cash, or a mixture. Either way, the target company equity is eliminated. The key takeaway here is to understand that Littleco equity is being eliminated – and that some Littleco shareholders have become Bigco shareholders (the $40 million in new equity issued by Bigco to Littleco), while some shareholders received cash in exchange for tendering their shares ($60 million which Bigco raised by borrowing from a bank).

Putting this all together, you would likely see something that looks like this in a model:

Deal Accounting Tutorial Conclusion

I hope this helps understand the basics of M&A accounting. There are many complexities to M&A accounting that we did not address here – treatment of deferred tax assets, creation of deferred tax liabilities, negative goodwill, capitalization of certain deal-related expenses, etc. Those are the issues we spend a great deal of time working through in our Self Study Program and live seminars, which I encourage you to participate in if you haven’t already.

Seller Financing

Seller Financing, or a “seller note”, is a method for buyers to fund the acquisition of a business by negotiating with the seller to arrange a form of financing.

Seller Financing in Homes and M&A Transactions

With seller financing, also known as “owner financing”, the seller of a business agrees to finance a portion of the sale price, i.e. the seller accepts a portion of the total purchase price as a series of deferred payments.

A significant portion of transactions involving the sale of homes and small to medium-sized businesses (SMBs) include seller financing.

Seller financing means the seller agrees to receive a promissory note from the buyer for an unpaid portion of the purchase price.

While less common in the middle market, seller financing does appear occasionally, but in far lower amounts (i.e. 5% to 10% of the total deal size).

Usually, the seller offers the financing if no other sources of funding can be obtained by the buyer and the transaction is on the verge of falling apart for that reason.

Seller Note in M&A Deal Structure (“Owner Financing”)

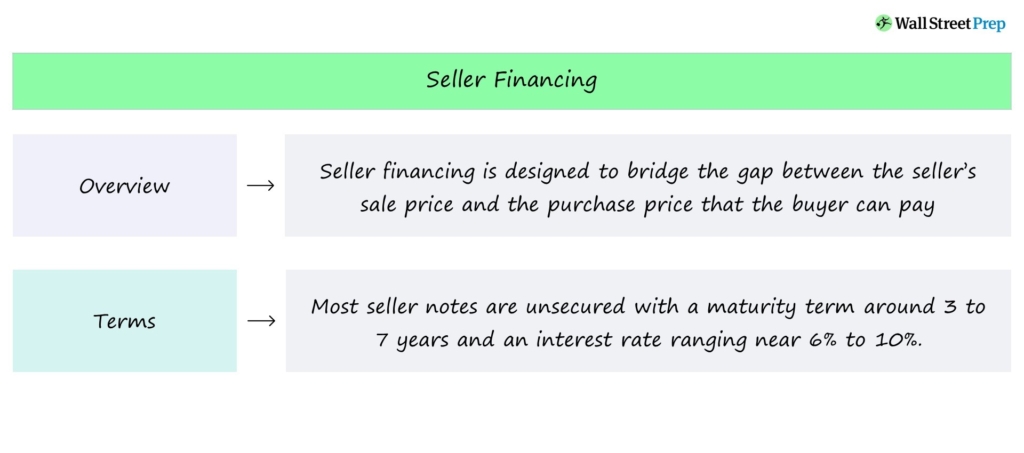

A seller note is designed to bridge the gap between the seller’s sale price and the amount that the buyer can pay.

However, there is substantial risk associated with providing financing to a buyer, especially since the seller is an individual with limited resources rather than an institutional lender.

The seller must carefully vet the buyer by requesting a credit report, calling personal references, or hiring a third party to run an in-depth background check.

If all goes well and the buyer fulfills all their debt obligations, the seller note can facilitate a quicker sale, despite the risk undertaken.

The process of applying for a bank loan can be time-consuming, only for the result to sometimes be a rejection letter, as lenders can be hesitant to provide financing to fund the purchase of a small, unestablished business.

Seller Financing Terms: Maturity Term and Interest Rates

A seller note is a form of financing wherein the seller formally agrees to receive a portion of the purchase price — i.e. the acquisition proceeds — in a series of future payments.

It is important to remember that seller notes are a type of debt financing, thus are interest-bearing securities.

But if there are other senior secured loans used to fund the transaction, seller notes are subordinated to those senior tranches of debt (which have higher priority).

Most seller notes are characterized by a maturity term of around 3 to 7 years, with an interest rate ranging from 6% to 10%.

- Maturity Term = 3 to 7 Years

- Interest Rate = 6% to 10%

Because of the fact that seller notes are unsecured debt instruments, the interest rate tends to be higher to reflect the greater risk.

Seller Financing in Home Sales: Real Estate Example

Suppose a seller of a home, i.e. the homeowner, has set the sale price of their house at $2 million.

- Home Sale Price = $2 million

An interested buyer was able to secure 80% of the total purchase price in the form of a mortgage loan from a bank, which comes out to a $1.6 million.

The buyer, however, only has $150k in cash, meaning there is a shortage of $250k.

- Mortgage Loan = $1.6 million

- Buyer Cash on Hand = $150k

- Buyer Shortage = $250k

If the homeowner decides to take the risk, the $250K gap in financing can be bridged through owner financing, typically structured as a promissory note (and the sale of the home could then close).

The seller and buyer will then negotiate the terms of the seller note and have them written out in a document that states the interest rates, scheduled interest payments, and the maturity date on which the remaining principal must be repaid.

Compared to traditional mortgages, seller financing tends to have higher down payments (~10% to 20%) and interest payments with shorter borrowing periods since the owner most likely does not want to be a “lender” for decades on end.