Types of M&A transactions

Attorneys with you, every step of the way

Count on our vetted network of attorneys for guidance — no hourly charges, no office visits.

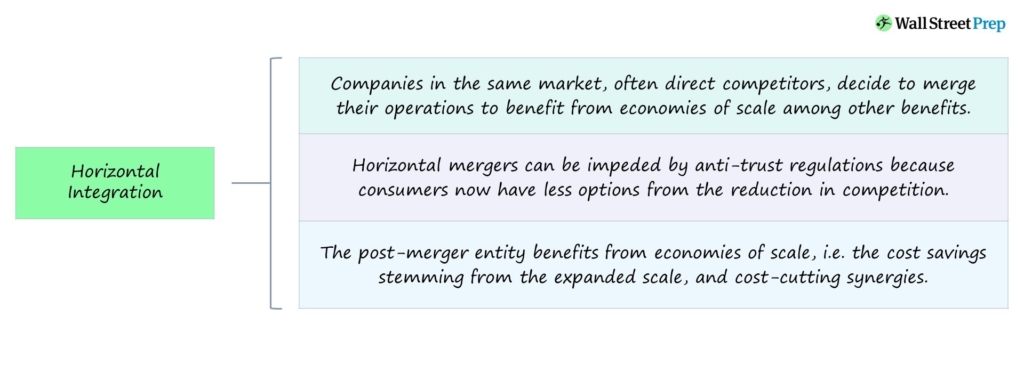

Horizontal Integration

Horizontal Integration occurs from mergers among companies directly competing in the same or closely adjacent markets.

The companies involved in a horizontal merger are normally close competitors that provide goods or services at the same level in the overall value chain.

Horizontal Integration – Merger Strategy

Horizontal integration is a type of merger where competitors operating in the same market combine their operations to benefit from economies of scale.

If two companies that offer virtually identical or similar goods or services decide to undergo a merger, the transaction is considered to be horizontal integration.

The horizontal integration strategy – in which two companies operate at the same level of the value chain and decide to merge – enables companies to increase in size and scope.

Together, the combined entity’s reach is far broader in terms of expanding into new markets and diversifying a consolidated portfolio of offerings.

The result is the creation of economies of scale, wherein the post-merger company obtains cost savings from the expanded scale.

- Economies of Scale → The cost per unit of output declines with increased scale up to a certain point

- Greater Production Output → The efficiencies related to production such as streamlined processes enable the company to produce a greater number of units at their manufacturing facilities.

- Buyer Power → The combined company can purchase raw materials in bulk for steep discounts and negotiate other favorable terms.

- Pricing Power → Given the limited number of competitors in the marketplace, the combined company can make the discretionary decision to increase prices (and the few other companies in the market then normally follow suit).

- Cost Synergies → The entity benefits from cost synergies, namely shutting down redundant facilities and duplicate job functions deemed to no longer be necessary.

Regulatory Risks of Horizontal Integration

If integrated properly, the profit margins of the merged company are most likely to increase, although the revenue synergies can take substantially more time to materialize (or may never actually occur).

The major risk associated with horizontal integration is the reduction in competition within the market in question, which is where scrutiny from regulatory bodies comes into play.

The benefits derived from the companies participating in the merger come at the expense of consumers and suppliers or vendors.

- Consumers: Consumers now have fewer options because of the merger while suppliers and vendors have lost more of their bargaining power.

- Suppliers and Vendors: The merged company possesses a greater proportion of the total market share, which directly causes its buyer power to increase and gives it more negotiating leverage over its suppliers, vendors, and distributors.

Of course, the risk of the merger failing to deliver the expected synergies is inevitable.

Horizontal mergers are therefore not without risk.

If the integration is done poorly – for example, suppose the differing cultures of the companies cause other issues – the result from the merger could be value-destruction, rather than value-creation.

Horizontal Integration and Oligopoly

Often, the economies of scale and cross-selling to each other’s customer bases as a result of horizontal integration can be the catalyst preceding the creation of an oligopoly, in which a limited number of influential companies hold most of the market share in an industry.

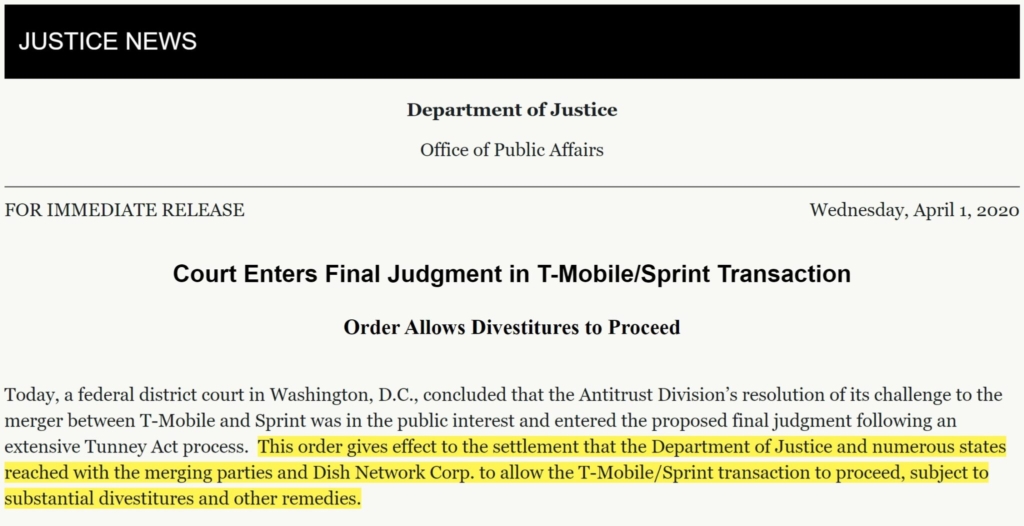

Sprint and T-Mobile Merger – Anti-Trust Suit and Controversy

Following the completion of a horizontal merger, competition in the market declines, which is typically brought to the attention of the appropriate regulatory bodies immediately. i.e. anti-trust concerns are the primary drawback to horizontal integration.

For example, the Sprint and T-Mobile merger is a relatively recent horizontal merger that was under heavy regulatory scrutiny.

The controversial merger was approved by the U.S. Justice Department and Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2020 after a multi-year anti-trust suit after the carriers agreed to divest certain prepaid wireless assets to satellite provider Dish.

The expectation was that Dish would subsequently create its own cellular network and maintain the number of competitors in the market.

Even as of the present date, the merger is criticized frequently as one of the worst, anti-competitive acquisitions that was approved and later resulted in widespread price increases from reduced competition, i.e. greater pricing power from market leadership and the limited number of market participants.

Horizontal Integration vs. Vertical Integration

In contrast to horizontal integration, vertical integration refers to a merger among companies at different levels of the value chain, e.g. upstream or downstream activities.

The companies involved in vertical integration each have their own unique role at different stages of the overall production process.

For instance, a car manufacturer merging with a producer of tires would be an example of vertical integration, i.e. the tire is a necessary input to the end product in a car production line.

The distinction between horizontal and vertical integration is that the former occurs among similar competitors, whereas the latter takes place between companies at different stages in the value chain.

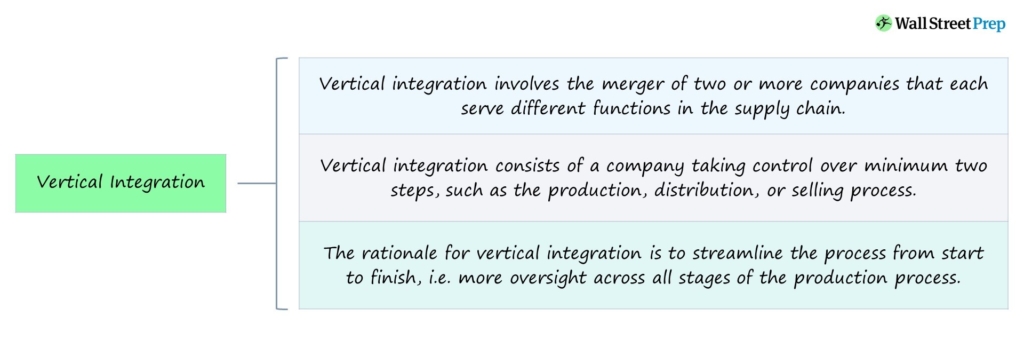

Vertical Integration

Vertical Integration involves the merger of two or more companies that serve different functions in the supply chain. In such a case, the entire (or most) of the supply chain is controlled by the company. Thus, the company receives increased oversight and control over the internal processes, which should theoretically eliminate operating inefficiencies.

Vertical Integration – Merger Strategy

How Vertical Integration Works (Step-by-Step)

Vertical integration consists of a company taking control over at least two steps in a given value chain, such as the production, distribution, or selling of the finished good or service, as opposed to outsourcing certain tasks.

The vertical integration of a supply chain implies that each step of the process is owned and closely controlled by a combined entity.

If a company publicly announces its plans to control and own aspects of its supply chain rather than relying on external suppliers as it did in the past, the shift is called “vertical integration”.

Furthermore, the merged company possesses a greater proportion of the total market share, which directly causes its buyer power to increase and gives it more negotiating leverage over its suppliers and distributors.

The end goal for pursuing vertical integration is to streamline the operational process from start to finish, i.e. having more ownership over all of the various stages in a production process.

Companies often opt to outsource or rely on external 3rd parties in an effort to reduce spending, yet sub-par production and quality issues can cause real damage to the branding of the company and diminish the trust of their customer base.

Therefore, vertical integration consists of a company possessing ownership over most, if not all, stages of the production cycle, including the suppliers and distributors.

Pros/Cons of Vertical Integration

Normally, the supply chain process starts with purchasing raw materials from suppliers – followed by a wide range of potential steps depending on the context – until the final product reaches the customer.

The strategy of vertical integration implies the company controls multiple stages in its supply chain, thereby reducing or even eliminating the need for reliance on any third parties.

Vertical integration can result in the production process becoming more efficient with reduced costs (and higher profit margins).

The drawback, however, is that there is a great number of initial costs that are required to build the infrastructure and purchase the necessary equipment. Until the company recoups the initial cost, the integration would remain unprofitable.

Ownership of the supply chain from start to finish might initially sound appealing, but more control over the process does not necessarily result in higher quality.

While factors such as communication may be improved, the management team must have a thorough plan in order to be capable of managing every step of the production process.

Having an inept management team responsible for overseeing the complex supply chain can be very risky.

Vertical Integration Example: Electronics Supplier Acquisition

Suppose an electronics company decided to purchase a supplier that they have worked closely alongside in the past, and those suppliers’ parts (and components) are crucial inputs to the device.

If the electronics company decides to purchase the supplier to reduce manufacturing costs and streamline its operations, the acquisition would be an example of vertical integration.

Additionally, another example of vertical integration includes purchasing trucks and fleets of vehicles to transport the parts, i.e. the company is now in control of the entire distribution process.

Types of Vertical Integration: Forward vs. Backward Integration

There are two types of vertical integration:

- Forward Integration → When an acquirer moves downstream; i.e. the company’s acquisition target moves them closer to the end customer, e.g. distributor or technical support.

- Backward Integration → When an acquirer moves upstream, the company is purchasing suppliers or product manufacturers (that are further away from the end customer).

A company undergoing backward integration is shifting its ownership and control of the process to an earlier point in the supply chain, whereas a company pursuing forward integration is moving forward to own and control the production stages that interact more closely with the end customers, such as the distribution process.

Vertical Integration vs. Horizontal Integration

Horizontal integration refers to a merger where competitors are combining their operations (and asset base) to benefit from economies of scale, increased buyer power over suppliers and vendors, and expanding their reach into new geographical locations (and end markets).

The differentiating factor between horizontal integration and vertical integration is that horizontal integration is the merger of close competitors operating in the same market.

On the other hand, vertical integration is between companies operating at different stages in the value chain and with distinct responsibilities in the production cycle.

In contrast to horizontal integration, vertical integration consists of a merger involving companies functioning at various levels of the value chain, such as either upstream or downstream activities.

Each company engaged in vertical integration has its own unique role at a specific stage of the production process.

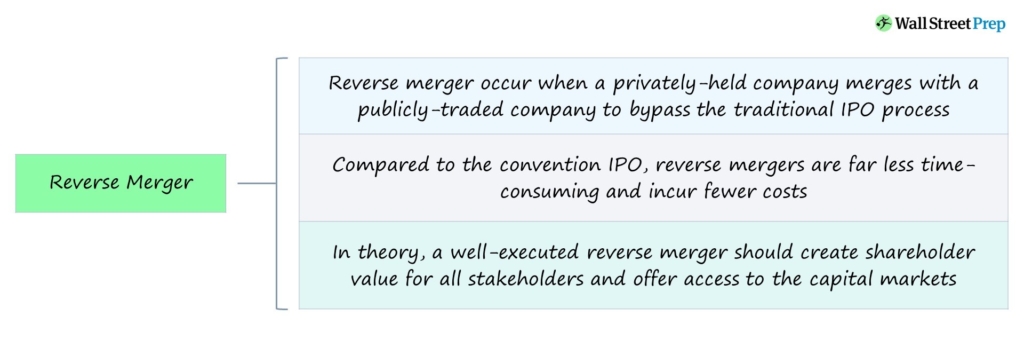

Reverse Merger

A Reverse Merger occurs when a privately-held company acquires a majority stake in a publicly-traded company. A reverse merger – or “reverse takeover” – is most often undertaken to bypass the traditional initial public offering (IPO) process, which can be time-consuming and costly.

Reverse Merger Transaction Process

In a reverse merger transaction, a private company obtains a majority stake (>50%) in a public company to gain access to the capital markets while circumventing the traditional IPO process.

Usually, the public company in a reverse merger is a shell company, meaning that the company is an “empty” company only existing on paper and does not actually have any active business operations.

Nevertheless, there are other instances in which the public company does indeed have ongoing day-to-day operations.

As part of the reverse merger, the private company acquires the publicly-listed target company by exchanging the vast majority of its shares with the target, i.e. a stock swap.

In effect, the private company essentially becomes a subsidiary belonging to the publicly-traded company (and is thereby considered a public company).

Upon completion of the merger, the private company obtains control over the public company (which remains public).

While the public shell company remains intact post-merger, the private company’s controlling stake enables it to take over the consolidated company’s operations, structure, and branding, among other factors.

Reverse Mergers – Advantages and Disadvantages

A reverse merger is a corporate tactic utilized by private companies seeking to “go public” – i.e. become publicly listed on an exchange – without formally undergoing the IPO process.

The primary advantage for a company to pursue a reverse merger instead of an IPO is the avoidance of the onerous IPO process, which is lengthy and costly.

As an alternative to the traditional IPO route, a reverse merger can be perceived as a more convenient, cost-efficient method to obtain access to the capital markets, i.e. public equity and debt investors.

In theory, a well-executed reverse merger should create shareholder value for all stakeholders and offer access to the capital markets (and increase liquidity).

The decision to undergo an IPO can be adversely affected by changing market conditions, making it a risky decision.

In contrast, the reverse merger process is not only significantly more cost-effective but can also be completed in a matter of weeks since the public shell company is already registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

On the other hand, reverse mergers have various risks, namely the lack of transparency.

The drawback to an expedited, quick process is the reduced time to perform due diligence, which creates more risk stemming from overlooking certain details that can turn out to be costly mistakes.

In a limited time frame, the companies involved (and their shareholders) must conduct diligence on the proposed transaction, but there is a significant time constraint for all parties engaged.

Moreover, the takeover of a private company is not always an easy process, since the existing stakeholders could oppose the merger, causing the process to be prolonged from unexpected obstacles.

The final disadvantage relates to the share price movement of the private company following the merger.

Given the limited time to conduct diligence and the reduced amount of information available, the lack of transparency (and unanswered questions) causes share price volatility, especially right after the transaction closes.

Reverse Merger Example – Dell / VMware

In 2013, Dell was taken private in a $24.4 billion management buyout (MBO) alongside Silver Lake, a global technology-oriented private equity firm.

Approximately three years later, Dell acquired storage provider EMC in 2016 for roughly $67 billion in a deal that effectively created the largest private technology company (renamed “Dell Technologies”).

Following the acquisition, the portfolio of brands included Dell, EMC, Pivotal, RSA, SecureWorks, Virtustream, and VMware – with the controlling stake in VMware (>80%) representing a crucial part of the reverse merger plans.

A couple of years thereafter, Dell Technologies began to pursue options to return to becoming a publicly listed company, offering a path for private equity backer Silver Lake to exit its investment.

Dell soon confirmed its intention to merge with VMware Inc, its publicly-held subsidiary.

In late 2018, Dell returned to trade under the ticker symbol “DELL” on the NYSE after the company repurchased shares of VMware in a cash-and-stock deal worth around $24 billion.

For Dell, the reverse merger – a complicated ordeal with several major setbacks – enabled the company to return to the public markets without undergoing an IPO.

In 2021, Dell Technologies (NYSE: DELL) announced its plans to complete a spin-off transaction involving its 81% stake in VMware (VMW) to create two standalone companies, marking the completion of Dell’s initial objective and the decision to now operate independently for the best interests of all stakeholders.

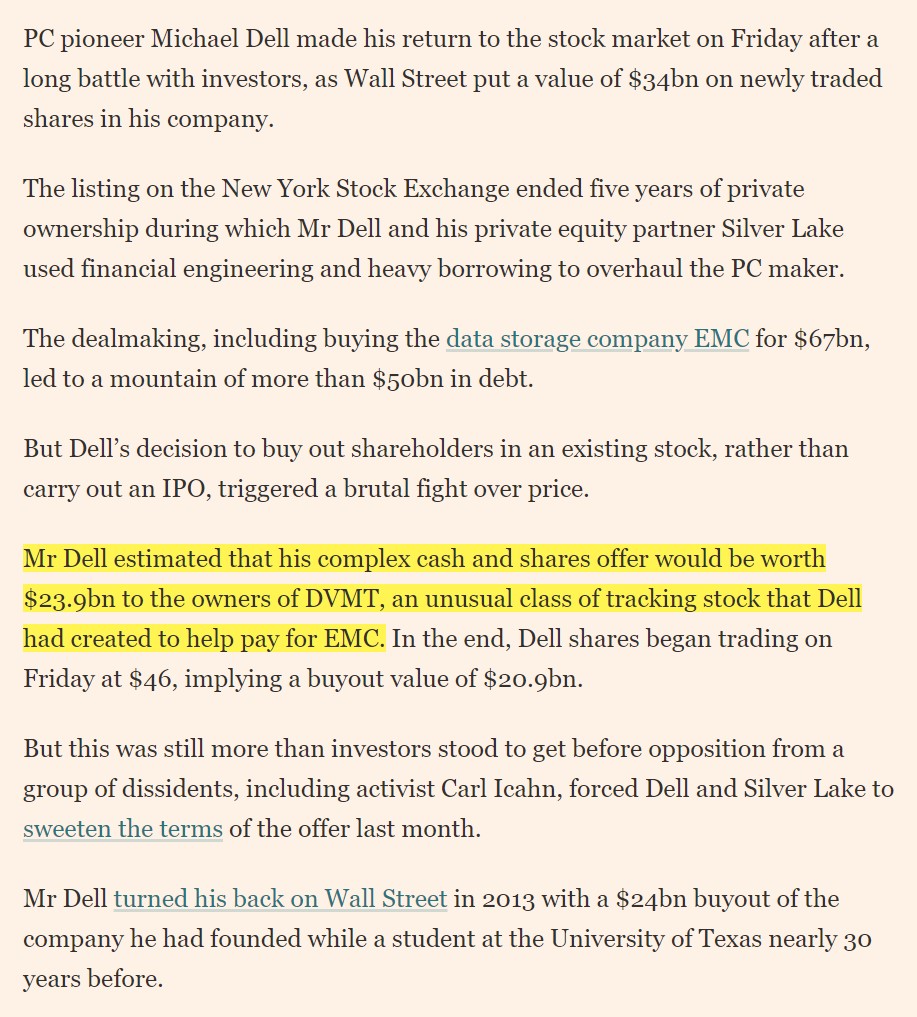

Conglomerate Merger

A Conglomerate Merger is the combination of two or more companies that each operate in distinct, seemingly unrelated industries.

A conglomerate merger strategy combines several different businesses, so the companies involved are not in the same industry nor direct competitors, yet potential synergies are still expected.

Conglomerate Merger Strategy in Business

The conglomerate merger strategy involves the combination of various different businesses with minimal operational overlap.

A conglomerate is defined as a corporate entity comprised of several different, unrelated companies, each having their own unique business functions and industry classifications.

Conglomerates are formed from conglomerate mergers, the combination of numerous companies that operate in different industries.

The merger occurs among businesses unrelated to each other, yet conglomerate mergers can still result in several strategic benefits to the consolidated entity.

Often, the anticipated synergies from such a merger become more apparent in periods of economic slowdowns.

Types of Conglomerate Mergers

Pure vs. Mixed Conglomerate Merger Strategy

In a horizontal merger, companies that perform the same (or closely adjacent) business functions decide to merge, whereas similar companies with different roles in the supply chain merge in a vertical merger.

In contrast, conglomerate mergers are unique in the sense that the companies involved perform seemingly unrelated business activities.

At a glance, the synergies might be less straightforward, yet such mergers can result in a diversified, less risky overall company.

Conglomerate mergers can be distinguished into two categories:

- Pure Conglomerate Mergers → The overlap between the companies combined is practically nonexistent, as the commonalities are minimal even from a broad perspective.

- Mixed Conglomerate Mergers → On the other hand, the mixed strategy involves companies where the functions are still different, but there are still a couple of identifiable aspects and shared interests, such as the expansion of their product offerings.

In the former, the companies post-merger continue to operate independently in their own specific end markets, while in the latter, the companies are different but still benefit from the extension of their overall reach and branding, among other benefits.

While the independent nature of the merger might seem like a drawback, it is precisely the objective of the transaction and where the synergies are derived from.

Conglomerate Merger Benefits

- Diversification Benefits → The strategic rationale for a conglomerate merger is most often cited to be diversification, wherein the post-merger company becomes less vulnerable to external factors such as cyclicality, seasonality, or secular declines.

- Less Risk → Considering there are now multiple different lines of businesses operating under a single entity, the conglomerate is less exposed overall to external threats because the risk is spread across the companies to avoid over-concentration in one specific part of the company. For instance, one company’s lackluster financial performance could be offset by the strong performance of another company, upholding the financial results of the conglomerate as a whole. Often, the reduced risk in the combined entity is reflected in a lower cost of capital, i.e. WACC.

- More Access to Financing → The lower risk attributed to the post-merger company also provides numerous financial benefits, such as the ability to access more debt capital more easily, under more favorable lending terms. From the perspective of lenders, offering debt financing to a conglomerate is less risky since the borrower is essentially a collection of companies, rather than only one company.

- Branding and Expanded Reach → The conglomerate’s branding (and overall reach in terms of customers) can also be strengthened by virtue of holding more companies, especially since each company continues to operate as an independent entity.

- Economies of Scale → The increased size of the conglomerate can contribute to higher profit margins from the benefits of economies of scale, which refers to the incremental decline in the per unit cost from greater volume output, e.g. business divisions could share facilities, close redundant functions such as sales and marketing, etc.

Risks of Conglomerate Mergers

The primary drawback to conglomerate mergers is that the integration of numerous business entities is not straightforward.

The process can be very time-consuming, meaning that it can take years before the synergies begin to materialize and positively impact the company’s financial performance.

The combination of two businesses could also lead to friction caused by factors such as cultural differences and an inefficient organizational structure – with the source often being a leadership team that cannot effectively manage all the companies at once.

Most of the risks associated with these sorts of mergers are out of the control of the management team, such as the cultural fit between the companies involved, making it even more necessary for each additional integration process to be well-planned, as mistakes can be costly.

Sum-of-the-Part Valuation (SOTP) of Conglomerate Business

In order to estimate the valuation of a conglomerate, the standard approach is a sum-of-the-parts (SOTP) analysis, otherwise known as a “break-up analysis”.

The SOTP valuation is typically performed for companies with numerous operating divisions in unrelated industries, e.g. Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A).

Since each business division of the conglomerate comes with its own unique risk/return profile, attempting to value the entire company together is impractical. As such, a different discount rate should be used for each segment, and a distinct set of peer groups for each division is used to perform trading and transaction comps.

Completing the valuation on a per-business-segment basis tends to result in a more accurate implied value, rather than valuing the company together as a whole entity.

The conglomerate is conceptually broken up and each business unit is valued separately in a SOTP analysis. Once an individual valuation is attached to each piece of the company, the sum of the parts represents the estimated combined worth of the conglomerate.

Divestiture

A Divestiture occurs when a corporation proceeds with either a partial or an outright sale of a business segment and the assets belonging to the unit.

Divestiture Definition in Corporate Finance

Divestitures in M&A are when a company sells a collection of assets or an entire business division.

Generally, the strategic rationale of divestitures include:

- Non-Core Part of Business Operations

- Misalignment with Long-Term Corporate Strategy

- Liquidity Shortfall and Urgent Need for Cash

- Activist Investor Pressure

- Anti-Trust Regulatory Pressure

- Operational Restructuring

The decision to divest an asset or business segment most often stems from management’s determination that insufficient value is contributed by the segment to the company’s core operations.

Companies should theoretically divest a business division only if misaligned with their core strategy, or if the assets possess more value if sold or operated as an independent entity than if retained.

For instance, a business division could be deemed redundant, non-complementary to other divisions, or distracting from core operations.

From the perspective of existing shareholders and other investors, divestitures can be interpreted as management admitting defeat in a failed strategy in that the non-core business fell short in delivering the originally expected benefits.

A divestiture decision implies that a turnaround of the division is not plausible (or not worth the effort), as the priority is instead to generate cash proceeds to fund reinvestments or to reposition themselves strategically.

How Divestitures Work (Step-by-Step)

After completing the divestiture, the parent company can reduce costs and shift its focus to its core division, which is a common issue that market-leading companies encounter.

If a merger or acquisition is poorly executed, the value of the combined entities is less than the value of the standalone entities, meaning that the two entities are better off operating individually.

More specifically, the acquisition of companies without a long-term plan for integration can lead to so-called “negative synergies,” wherein shareholder value declines post-deal.

In effect, divestitures could leave the parent company (i.e. the seller) with:

- Higher Profit Margins

- Streamlined Efficient Operations

- Greater Cash on Hand from Sale Proceeds

- Focus Re-Aligned with Core Operations

Divestitures are thereby a form of cost-cutting and operational restructuring – plus, the divested business unit can unlock “hidden” value creation that was hindered by being mismanaged by the parent company.

Activist Investors and Divestitures: Value Creation Strategy

If an activist investor sees a certain business segment has been underperforming, a spin-off of the unit could be pitched to improve the parent company’s profit margins and let the division thrive under new management.

Many divestitures are thus influenced by activists pushing for the sale of a non-core business and then requesting a capital distribution to shareholders (i.e. direct proceeds, more cash for reinvestments, more focus by management).

Divestiture Example: AT&T Monopoly Break-Up (NYSE: T)

Anti-trust regulatory pressure can result in a forced divestiture, typically related to efforts to prevent the creation of monopolies.

One frequently cited case study for anti-trust divestitures is the break-up of AT&T (Ma Bell).

In 1974, the U.S. Justice Department filed an anti-trust lawsuit against AT&T that remained unresolved until the early 1980s, in which AT&T agreed to divest its local-distance services as part of the landmark settlement.

The divested regional units, collectively called the “Baby Bells,” were newly-formed telephone companies created after the anti-trust suit against AT&T’s monopoly.

In hindsight, the forced divestiture is criticized by many as the suit only reduced the roll-out of high-speed internet technologies for all U.S. consumers.

Once the regulatory environment in the telecommunications sector loosened, many of those companies returned to being part of the AT&T conglomerate, alongside other cellular carriers and cable providers.

The prevalent view is that the break-up was unnecessary, as the “deregulation” that forced AT&T to be broken up just led to the company only becoming a more diversified, natural monopoly.

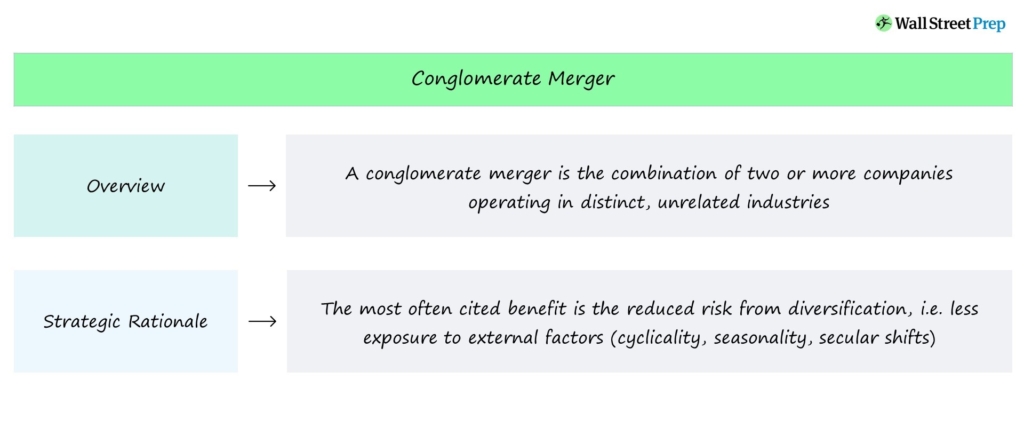

Types of Divestitures: Corporate Transactions

A wide range of different transaction structures could be categorized as divestitures. However, the most common variations of divestitures are the following:

- Sell-Off: In a sell-off, the parent exchanges the divested assets to an interested buyer (e.g. another company) in return for cash proceeds.

- Spin-Offs: The parent company sells a specific division, i.e. the subsidiary, which creates a new entity that operates as a separate unit where existing shareholders are given shares in the new company.

- Split-Ups: A new business entity is created with many similarities as a spin-off, but the distinction lies in the distribution of shares, as existing shareholders have the option to either keep shares in the parent or the newly created entity.

- Carve-Out: A partial divestiture, carve-outs refer to when the parent company sells off a piece of the core operations through an initial public offering (IPO) and a new pool of shareholders is established – further, the parent company and the subsidiary are legally two separate entities, but the parent will typically still retain some equity in the subsidiary.

- Liquidation: In a forced liquidation, the assets are sold in pieces, most often as part of a Court ruling in a bankruptcy proceeding.

Asset Sales in Restructuring (“Fire Sale” M&A)

Sometimes, the rationale behind a divestiture is related to preventing the company from restructuring its debt obligations or filing for bankruptcy protection.

In such scenarios, the sale tends to be a “fire-sale” where the objective is to get rid of the assets as soon as possible, so the parent company has enough proceeds from the sale to meet scheduled payments to suppliers or debt obligations.

Divestiture vs. Carve-Out

Oftentimes, carve-outs are referred to as a “partial IPO” because the process entails the parent company selling a portion of their equity interest within the subsidiary to public investors.

In practically all cases, the parent holds a substantial equity stake in the new entity, i.e. usually >50% – which is the unique feature of carve-outs.

Upon completion of the carve-out, the subsidiary is now established as a new legal entity run by a separate management team and board of directors.

As part of the initial carve-out plan, the cash proceeds from the sale to 3rd party investors are then distributed to the parent company, the subsidiary, or a mixture.

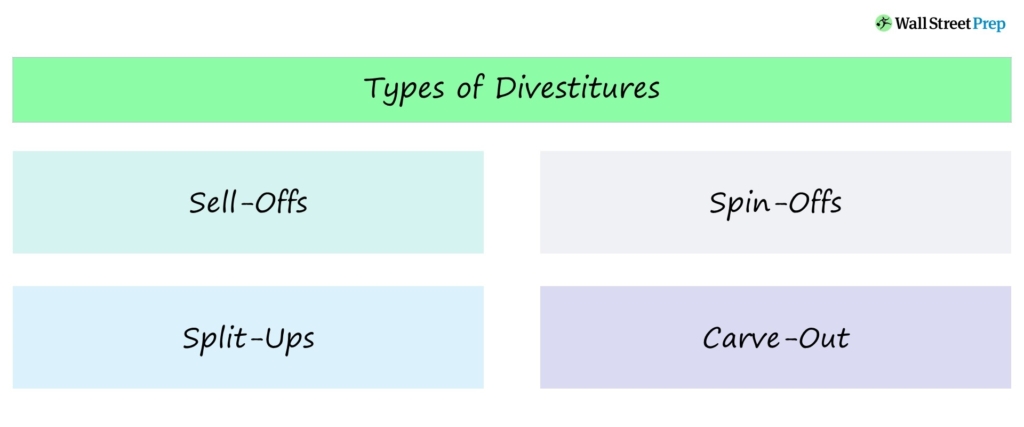

Spin-Off

A Spin-Off refers to when a parent company sells a specific business unit or division, i.e. a subsidiary, to effectively create a new standalone company.

As part of the spin-off, the parent company’s existing shareholders are given shares in the new independent company.

Spin-Off Corporate Action

How Spin-Offs Work in Finance

A spin-off refers to the formation of an independent entity, in which shares of the subsidiary are distributed among the shareholders of the parent company.

In a spin-off — a type of divestiture performed by corporations — the parent company separates a particular division in order to create an independent entity.

As a newly formed, independent entity, the business unit will have its own set of new shares (and ownership claims).

The existing shareholders receive shares in proportion to their original ownership percentage in the company, i.e. on a pro-rata basis, and in the form of a non-cash special dividend.

Therefore, the number of shares received by an existing shareholder is directly a function of the number of shares the shareholder held in the parent company.

After completion of the spin-off, it is the decision of the shareholders on whether to continue to hold those new shares or to sell them in the open market.

Further, the business entity that was previously operating under the parent company now has its own management structure; it is now set up and recognized as an independent company.

Learn More → Spin-Offs (SEC)

Spin-Off Strategic Rationale

The rationale for spin-offs is most often in response to pressure from shareholders on the board of directors to divest a specific subsidiary or business segment.

The subsidiary, from their viewpoint, may be better off operating as a standalone company over the long run, i.e. unlocking hidden value currently hindered by being under a parent company.

In theory, spin-offs increase shareholder value by increasing the value of the parent by virtue of removing a business line that no longer fits with the core structure of the company.

The parent company itself might also be held back by the subsidiary due to a misalignment with its core operations — hence, activist investors that seek to identify and take a more hands-on approach to force management’s hand is another common catalyst for spin-offs.

Moreover, a company often performs a spin-off when its financial performance is underwhelming, so the sale could even be a necessary action to generate cash, i.e. a form of operational restructuring.

The spun-off companies are typically expected to be worth more as independent entities than as parts of a larger business, i.e. the sum of the parts is greater than the whole.

At the end of the day, the spin-off must be expected to create shareholder value in order to be approved.

Spin-Off Example — eBay and PayPal

One well-known example of a spin-off was between eBay and PayPal in mid-2015.

eBay, an e-commerce company, decided it was in the best interests of all stakeholders for the two companies to operate separately.

Previously, PayPal — the financial payment processing company — had been acquired by eBay and had been a subsidiary since.

In 2015, it was announced that eBay’s board of directors had approved the move for the separation of eBay and PayPal into two independent, publicly-traded companies, with a distribution of PayPal shares on a pro-rata basis to eBay’s shareholders.

As part of the distribution, eBay’s shareholders received one common share of PayPal for each share of eBay as of the date ending July 8, 2015, the set record date for the distribution.

Following the completion of the distribution, PayPal would trade under the ticker symbol “PYPL” as an independent company on the NASDAQ, whereas eBay would continue to trade under the ticker “EBAY”.

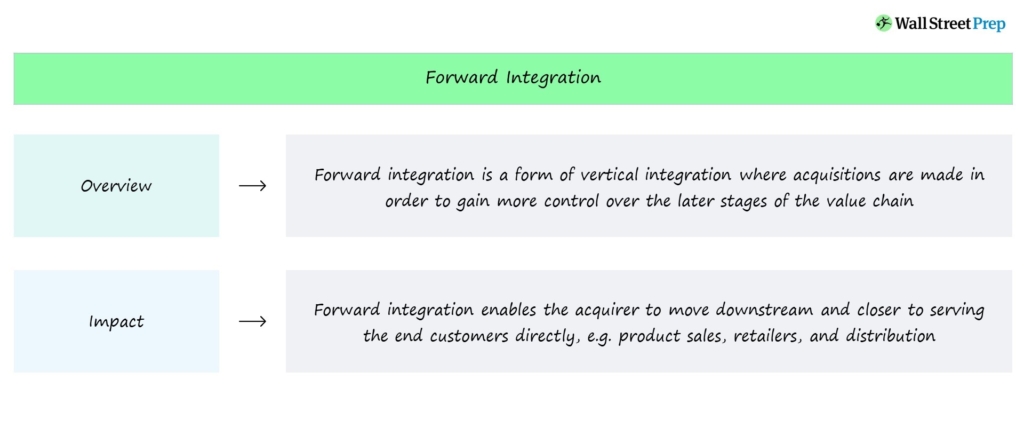

Forward Integration

Forward Integration is a strategy wherein a company obtains more control over activities that occur in the later stages of the value chain, i.e. “moving downstream”.

From forward integration, the company can possess more direct ownership over the later phases of the supply chain that are closer to the end customer rather than relying on another party to do so.

Forward Integration Strategy in Business

How Forward Integration Works (Step-by-Step)

Forward integration, a form of vertical integration, is when a strategic acquirer moves downstream, which means that the company becomes closer to interacting directly with its end customers.

Forward integration represents strategic acquisitions completed in order to gain more control over the later stages of the value chain.

Common examples of business functions considered to be “downstream” are distribution, technical support, sales, and marketing.

- Distribution

- Retailers

- Product Sales and Marketing (S&M)

- Customer Support

Most companies must initially partner with other third parties to outsource the delivery of certain services for the sake of time, convenience, and cost savings.

But once a company has reached a certain size and determines there to be enough opportunities to derive more value in downstream activities, forward integration can be the right course of action to pursue.

In effect, the company either acquires the third parties that performed the actions that they intend to take over, or the company can decide to build the operations in-house using their own funds to essentially compete with those third parties (and those external business relationships are phased out).

Forward Integration vs. Backward Integration

The other type of vertical integration is termed “backward integration.”

In contrast, backward integration – as implied by the name – is when an acquirer moves upstream to gain control of functions further away from the end customer.

- Forward Integration → The acquirer moves downstream, so the purchased companies enable the company to move closer to the end customer and manage those relationships more directly. In effect, the company can directly serve its end markets and establish a closer connection with its customers through active engagement.

- Backward Integration → The acquirer moves upstream, so the company in such a case is purchasing its suppliers or manufacturers of products (e.g. outsourced manufacturers). But in backward integration, the company’s responsibilities are shifting more to serve their end markets indirectly by focusing on controlling the product, which generally tends to consist of more technical functions such as product development and manufacturing.

Forward Integration Example

Manufacturer After-Sale Support Services

Suppose a manufacturer that formerly outsourced the distribution of its products to third parties decides to acquire the distributor.

Since the manufacturer is now directly in control over the distribution of the products they create, the acquisition would be considered an example of “forward” integration.

The downstream movement can frequently offer more opportunities related to after-sale service support, upselling, cross-selling, and more, so manufacturers are nowadays attempting to “remove the middleman” and increase their recurring revenue.

By virtue of becoming closer to the customer, the strategic integration presents more opportunities to build direct relationships with customers and offer other services, such as repairs and product support.

Formerly, the manufacturer’s priority was on the initial sale, i.e. one-time purchases by customers, meaning that their role in the value chain was to ensure product quality, maximize operating efficiency, and meet output requirements.

Similarly, acquiring or perhaps developing in-house the ability to perform the tasks done by wholesalers and retailers would also be examples of forward integration.

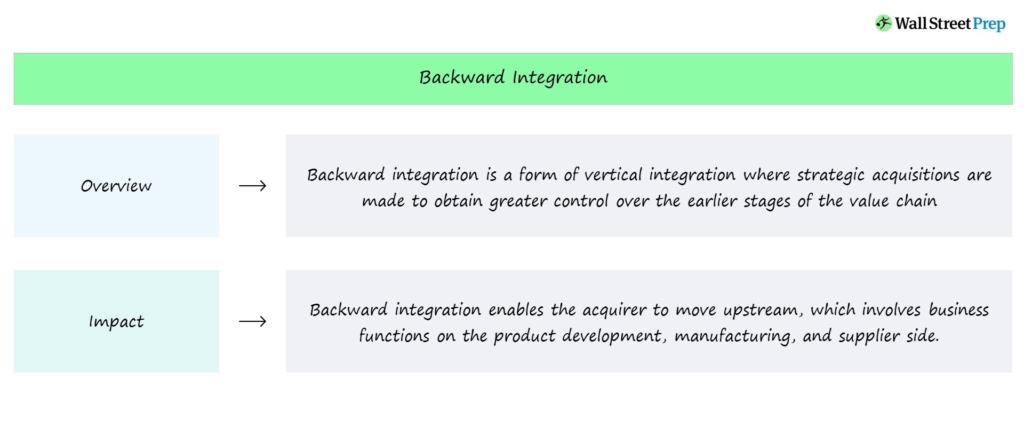

Backward Integration

Backward Integration is a strategy where a company gains more control over the functions in the earlier stages of the value chain, i.e. moving “upstream”.

The backward integration strategy results in the acquirer moving further away from serving its end customers. Therefore, the purchased companies would consist of functions such as product manufacturing, development, and supplying raw ingredients.

Backward Integration – Vertical Integration Strategy

How Backward Integration Works (Step-by-Step)

Backward integration, one of the two types of vertical integration, occurs when a strategic acquirer moves upstream, i.e. closer to the product manufacturing and supplier aspects of the value chain.

Upon completion of the acquisition, the company moves further from serving its end markets directly and is now more oriented around product development and manufacturing.

Backward integration strategies are completed to obtain greater control over the earlier stages of the value chain, which encompass the functions performed by specialized manufacturers and suppliers.

Common examples of business activities categorized as downstream functions are as follows.

- Product Manufacturing (i.e. Parts, Components)

- Research and Development (R&D)

- Raw Material Supplier

- Commodity Producers

As a result of backward integration, the acquiring company obtains more control over the earlier phases of the supply chain cycle, which refers to the manufacturing and supply side of the process.

Most often, companies that outsource manufacturing to third parties develop products that are highly technical and require an extensive number of parts or components.

Therefore, it can be more cost-efficient to outsource those tasks to third parties that specialize in developing those parts and components, especially since many of those companies operate overseas where labor is cheaper.

Once a company reaches a certain size and has enough funds, however, it can decide to pursue backward integration to obtain more ownership over the entire production process.

Direct ownership over those processes does not guarantee higher quality products by any means, but the opportunity is present where the company can manage the process and quality internally, i.e. resulting in less reliance on external parties.

Acquisition Strategy vs. In-House Build

While companies often opt to acquire and take over third parties, an alternative strategy is to build the required operations in-house.

However, building in-house operations to perform technical tasks can be costly and time-consuming, which is most often the reason for outsourcing in the first place.

Still, certain companies with enough funds and resources in terms of technical capabilities and employees (and the formation of a dedicated division) choose to proceed with in-house development instead of pursuing acquisitions.

Backward Integration vs. Forward Integration

The other type of vertical integration is “forward integration”, which describes companies moving closer to the end customers.

- Backward Integration → The company moves upstream and acquires suppliers or manufacturers of the product that the company sells.

- Forward Integration → The acquirer moves downstream and purchases companies that work closer to its end customers.

Forward integration, as implied by the name, results in the company moving closer to directly serving its end customers, such as product sales, distribution, and retailing.

Generally speaking, the functions closer to the customer tend to be less technical but represent more opportunities for active engagement and relationship-building with the customer base.

In contrast, backward integration involves greater control over upstream activities, which are further away from the end customers (in many cases, those upstream companies might not even be recognized by end customers).

Moreover, upstream activities like product development and manufacturing are more technical (i.e. R&D oriented) and contribute more to the product quality and its capabilities.

While certain companies seek to become closer to the end customer, such as a manufacturer offering more after-sale support services, other companies would rather prioritize ensuring the highest product quality by better controlling the product development and manufacturing side.

Backward Integration Example: Apple M1 Chips (AAPL)

One recent real-life example of backward integration is Apple (AAPL), which in the past couple of years has gradually become less reliant on chip makers and manufacturers of their product components.

Of course, Apple will realistically always continue to rely on outsourcing to some extent, given how technical its products are (and would probably never have full control over its entire value chain).

But in 2020, Tim Cook – the CEO of Apple – publicly announced Apple’s intention to part ways with Intel and confirmed rumors that the company would transition toward using its own custom-built ARM processors in its laptops and desktops.

In summary, Apple decided to build its own proprietary chips, M1, in-house rather than relying on Intel.

Apple-Intel 15 Year Partnership Ending

“Apple announced three new Mac computers on Tuesday: a MacBook Air, a 13-inch MacBook Pro, and a Mac Mini. They essentially look the same as their predecessors.

What’s new this time is the chip that runs them. Now they’re powered by Apple’s M1 chip instead of Intel processors. Tuesday’s announcement marks the end of a 15-year run where Intel processors powered Apple’s laptops and desktops, and a big shift for the semiconductor industry.”

– “Apple is Breaking a 15-year Partnership with Intel on its Macs” (Source: CNBC)

The Apple Silicon chips, per statements made by Apple, would facilitate more powerful Macs, and developing their own advanced chips would increase performance speed and extend battery life (and be more energy-efficient as a result of additional power management capabilities).

The first Mac with Apple Silicon was released in late 2020, and Apple expects to separate from Intel – for these particular components – in a gradual phase-out that’ll take approximately two years.

And on schedule, in the fall of 2022, news sources reported that Apple had removed the last remaining traces of Intel Silicon from its Mac product line.

Merger Arbitrage

What is Merger Arbitrage?

Merger arbitrage is an investment strategy that seeks to profit from the uncertainty that exists during the period between when an acquisition is announced and when it is formally completed.

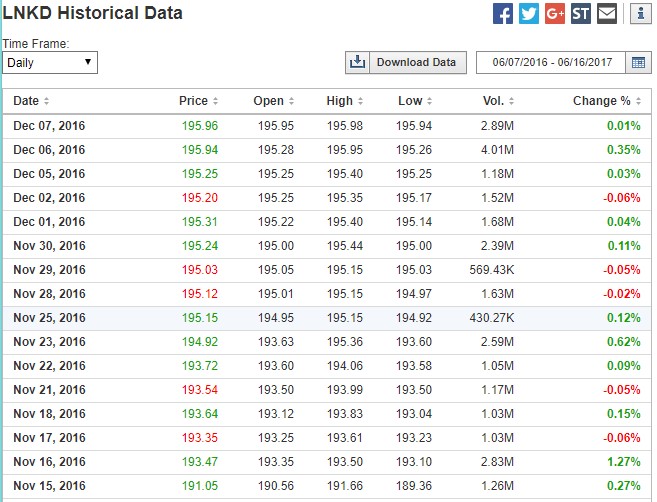

A simple merger arbitrage example will illustrate this: On June 13, 2016, Microsoft announced its acquisition of LinkedIn, offering $196 for each LinkedIn share.

On the announcement date, LinkedIn shares jumped from the $131.08 pre-announcement price to close at $192.21.

Merger Arbitrage: Real-World M&A Example

Microsoft Acquisition of LinkedIn

The question here is, “Why did LinkedIn shares stop short of $196?”

The period between when a deal is announced and when it closes (and LinkedIn shareholders actually get their $196) can last several months. During this period, LinkedIn shareholders still have to vote to approve the deal and the companies still need to secure regulatory approvals and file a whole bunch of legal paperwork.

The spread between the $192.21 and the $196.00 reflects the perceived risk that the deal will not go through. As we can see, by December, as the LinkedIn deal inched towards close, traders bid up the value to $195.96:

Risk Arbitrage Analysis (“Event-Driven Investing”)

The trading strategy of buying up target shares on the news of an announcement and waiting until the acquirer pays the full amount at the closing date is called “merger arbitrage” (also called “risk arbitrage”) and is a type of “event-driven” investing. There are hedge funds dedicated to this.

Here’s the basic idea. As you can see below , if you bought LinkedIn at announcement and waited, you’d make an annualized return of 4.0%.

The potential return here is low because, as you’ll see shortly, the risk of the deal falling through is low.

For deals where there’s significant antitrust or other regulatory risk (such as AT&T/Time Warner) or risk that shareholders won’t vote to approve the deal, shares don’t come as close to the purchase price.